Stephen Cobb, Senior Security Researcher at ESET examines the world of cyber crimes that is becoming bigger everyday and undermining the benefits of digital technology.

Are you in the market for stolen data? How about some tools to help you steal data or make money by hijacking other people’s computers? Well you’re in luck. It is now easier than ever to engage in cybercrime thanks to “next generation” dark markets.

A dark market is defined here as a website that enables the buying and selling of illegal goods, typically on a subset of the internet that doesn’t show up on Google or Bing, but is still fairly easy to find (more on that later). This article illustrates how far these markets have “evolved” in recent years, making cybercrime easier than ever.

Aspiring cybercriminals can now avoid risking their money doing deals with shady characters in obscure corners of cyberspace. Today’s dark markets come with star ratings, customer reviews, guarantees and buyer ratings. Product offerings are listed in easy-to-navigate digital store-fronts that make it a breeze to find exactly what you’re looking for; think Amazon or eBay for criminals.

Why go there?

Hopefully, you are not in the market for stolen data or other illicit digital goodies, so why am I telling you this? I have several reasons. First, an important part of my job is to make sure that companies and consumers and governments understand just how serious the cybercrime problem has become. I have found that showing people the websites where stolen data and crime tools are bought and sold really helps to get the message across, particularly when they see how “professional” and “serious” these pages look. Here is an example so that you can see what I mean:

Items for sale include malicious code for crimes like stealing information and cryptocurrency, illicitly logging keystrokes, and stealthily generating cryptocurrency (cryptojacking). You can see that ransomware and denial of service products are also on offer.

Items for sale include malicious code for crimes like stealing information and cryptocurrency, illicitly logging keystrokes, and stealthily generating cryptocurrency (cryptojacking). You can see that ransomware and denial of service products are also on offer.

Note that vendors are ranked and rated, as are products. Buyers pay in hard-to-trace cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin. Payments are often held in escrow until the buyer confirms that the transaction is satisfactory. You frequently see Help buttons, detailed FAQs, and Support options; sometimes there is Live Chat. Here is another market in which I have searched for “dumps” or collections of stolen payment card data that are bundled for sale:

Note that there are nearly 7,000 results and so – like any thoroughly modern digital market – there are plenty of ways to narrow your search with filters. For example, you can limit yourself to dumps that are sold through an escrow system.

Also note that, while the market seen above has nearly 60,000 listings under “Digital Goods”, it has even more under “Drugs”. Some dark markets just sell drugs, while others traffic in everything from pills and pot to stolen payment cards and pornography, possibly with a side order of firearms.

Shops that specialize in selling stolen payment card data have evolved from what used to be called carding forums. These days carding sites are no longer text-based backwaters of the internet. Some are out in the open and feature slick websites and aggressive advertising campaigns, like this one from Carding Mafia.

Gangster imagery is widely used in these banner ads, as are photos of celebrities. Here are some more examples – can you spot the TV personality referenced here, besides President Trump?

Gangster imagery is widely used in these banner ads, as are photos of celebrities. Here are some more examples – can you spot the TV personality referenced here, besides President Trump?

As you can see, these markets sell more than just the major credit cards. They also sell compromised eBay and PayPal accounts and – while it is not obvious here – they offer Amazon accounts as well (folks in the business will know that SLILPP, seen in that last ad, specializes in Amazon accounts).

What’s Next Gen about today’s cybercrime markets?

At this point, seasoned veterans of the internet may be grumbling that there is nothing new about online trafficking in stolen payment card data and other illegal items. And they would be right, but what is different today – different enough to warrant the use of the term Next Generation, if only cynically – is the degree to which dark markets have embraced the same technologies and techniques as legitimate online businesses, from customer reviews and branding to the machinery of marketing, like banner ad campaigns. Here is an example of a site where carding stores vie for attention – and these ads are running right out in the open on the regular internet:

In my opinion, this normalized approach to cybercrime qualifies as “next generation” because it has transformed an obscure, niche activity into an accessible business model. What we are seeing is a brand new sector of industry, one that appears to be thriving, despite the fact that it is fundamentally unethical and poses a serious threat to human progress.

If people can post holiday specials on crime tools and criminal activity, in the open, with little fear of retribution, then may it is time to recognize that a line has been crossed. Consider this carding website that was giving away stolen credit card details – in this case an Amex card – in celebration of Black Friday.

The impression you get is that engaging in cybercrime is a legitimate – if slightly edgy – business proposition; and in some parts of the world that is how it is perceived. Frankly, until the governments of the world do more to address this situation, there is little reason to think that efforts to reduce the negative impact of cybercrime on society will succeed.

The impression you get is that engaging in cybercrime is a legitimate – if slightly edgy – business proposition; and in some parts of the world that is how it is perceived. Frankly, until the governments of the world do more to address this situation, there is little reason to think that efforts to reduce the negative impact of cybercrime on society will succeed.

To be clear, there have been some successful law enforcement efforts in the past. There was the sting carried out by the FBI under the name Operation Card Shop; it began in 2010 and resulted in 26 arrests. Agents created a fake carding forum called CarderProfit in order to “identify users who were buying and selling stolen credit card accounts and goods purchased with stolen accounts” (Krebs on Security). Then, in 2013, a joint operation by the FBI and IRS took down an infamous dark market called “Silk Road.” That site was selling drugs and weapons as well as malware and payment card data; its creator is now serving a life sentence in prison.

While strong sentences may deter some would-be criminals, right now many more will continue to assume that the odds of getting caught committing crimes in cyberspace are slim. The way to increase those odds is to prosecute a lot more perpetrators and bring indictments more quickly. As criminologists studying “meatspace” crimes like burglary will tell you: swift justice is a much better deterrent than harsh sentences.

Don’t go there

I began by saying that I had two reasons for showing people the dark markets. The first was to raise awareness of the scale of the cybercrime problem. The second is to save people the trouble of going into these markets themselves. After a big data breach announcement – like the one last week from Marriott – a lot of people will be wondering: what happens to the stolen data? The short answer is that, in many cases, it ends up for sale in dark markets. Some people then ask how to get into the dark markets to take a look for themselves.

While the instructions for getting to dark markets are easily found on the regular internet, using your favorite search engine, it is safer to have someone show you screenshots of what you will find there, rather than go there yourself. As a general rule, the further you stray from the mainstream websites on the regular internet, the greater the risk that something unpleasant is going to happen, ranging for seeing disturbing images to getting compromised by malicious code. When it comes to perusing websites that sell illegal goods, you have the added risk of surveillance by law enforcement agents, for whom the phrase “I was only looking” may not carry much weight.

(I have no desire to sound elitist, but unless you have a good understanding of operational security and know your way around technologies like tunneling and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), visiting anywhere that is trafficking in stolen data or malware is just a bad idea.)

Dark markets as cybercrime infrastructure

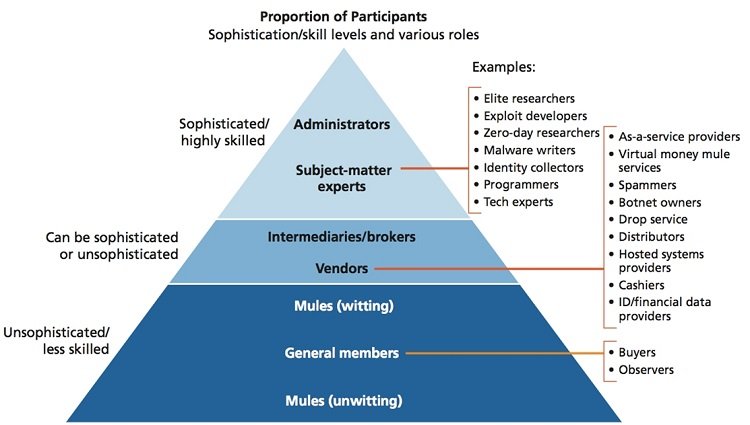

As I mentioned earlier, while today’s dark markets are decidedly more accessible and evolved than earlier iterations, the underlying activity they represent has been going on for most of this century in one form or another. One of the best studies of the phenomenon is the detailed 80-page report that RAND published in 2014: Markets for Cybercrime Tools and Stolen Data: Hackers’ Bazaar, by Lillian Ablon, Martin C. Libicki, and Andrea A. Golay. Here is how they represent the structure of cybercrime markets:

I often use this diagram to illustrate how “organized” this activity has become and, as a consequence of the lack of progress in disrupting it, how “established”.

I often use this diagram to illustrate how “organized” this activity has become and, as a consequence of the lack of progress in disrupting it, how “established”.

Carrying out most of the roles you see in this diagram requires access to computing capabilities. So I will end this article with an example of what we might all “cybercrime infrastructure” namely stolen servers. In the following screenshot you can see one of the places that criminals go when they need a deniable and disposable computer. Suppose your cybercrime operation needs a server to host some stolen data that you are selling. How about a machine running Windows Server 2012 RS, one with a fast internet connection. Here you can see some examples listed “for sale” in a dark market:

What you are buying here is remote access to a system that belongs to someone else, in other words, unauthorized access, very likely obtained illegally. As you can see, the site allows you to be very specific in your searches, depending on what you need. In this case the prospective customer is looking for administrative access to machines with a fixed internet address (IP).

The operators of this market disclaim any responsibility for what you do with your purchases; however, it is clear that the market is populated by sellers who have hacked the remote access credentials of their victims’ systems. As the website points out in its help pages, such machines can be useful when creating accounts at online banks, stores, payment systems, and so on. They can also be used for sending spam and setting up landing pages for your phishing emails. And of course “RDP with direct IP can be used as a VPN server or socks-proxy” to help hide your tracks (where RDP stands for Remote Desktop Protocol).

If they are suitably configured, stolen systems can be used to run password cracking software and cryptocurrency mining programs. What else? Well, you could just steal any useful information you find on the machine to which you have purchased access, or encrypt it using ransomware. In fact, compromised machines running RDP have become a serious attack vector for purveyors of ransomware (I explore this problem, and some solutions, in Ransomware and the enterprise: A new white paper).

The bottom line

In this article we have reviewed just a few slices of the thriving business that is cybercrime today. Absent drastic improvements in the way the world addresses the root causes of criminal activity in cyberspace, it is likely to continue unabated for some time, effectively undermining the benefits of digital technology. That means our efforts to protect systems and data from criminal abuse must also continue. Good security practices, including cyber-hygiene, must become universal. Security vendors must continue to improve their solutions. And we should work towards making the aforementioned drastic improvements come to pass.